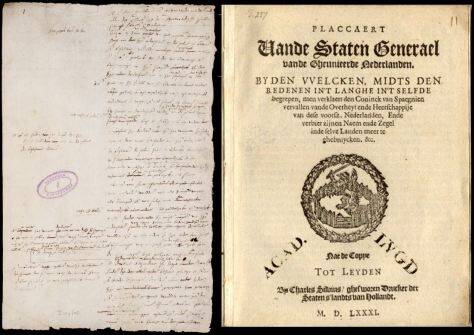

Full of admiration, Obama, the Dutch prime minister and Rijksmuseum director Pijbes stood looking at a copy of the 1581 Plakkaat van Verlatinge on March 24, 2014. During the U.S. president's lightning visit to our country for the Nuclear Summit, he had been dropped briefly by helicopter at Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum to admire Holland's showpieces, first and foremost, of course, Rembrandt's highly overrated The Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburgh getting ready to march out. But in addition to that “Night Watch,” Obama had to and would be confronted with the prototype of the American Declaration of Independence two centuries later.

This Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776 is a sacred document in the US. It is an integral part of education; entire programs have been developed to imbue students with the meaning of this special but unruly piece. In the Netherlands, such a cult around the Plakkaat will not arise lightly. However, our hereditary head of state, who is after all a doctoral student in history, did seem to be out for a reappraisal when he said at his inaugural address a year earlier, April 30, 2013, "The King holds his office in the service of the community. That deep-rooted realization was enshrined as early as 1581 by the States General in the Plakkaat van Verlatinghe, the birth certificate of what later became the Netherlands.' Wisely, he omitted the sequel, which expressed - albeit veiled - the idea that ultimately the “people” grant a sovereign his mandate.

Philip was no shepherd

Like a true manifesto, the Plakkaat begins with a bold declaration of principles. It reads (retranslated, interspersed with a piece of the original): "It is known to everyone that a sovereign is appointed by God to the head of his subjects in order to guard and protect them from all injustice, nuisance and violence, like a shepherd to guard his sheep. The subjects are not created by God for the service of the Sovereign to be submissive to him in everything he commands - God-pleasing or ungodly - right or wrong, and to serve as slaves "maer den Prince (is appointed) for the sake of the subjects, without whom hy egheen Prince en is. So the prince rules by the grace of his subjects. This is different language than the ‘By the grace of God King of the Netherlands’ in the salutation of royal decrees today.

The Pledge further demands of the sovereign that he must protect and love his subjects like a father his children and - again - like a shepherd his sheep. If he does not do this, but sets out to oppress them, cause them inconvenience, deprive them of their ancient freedom, rights and ancient traditions, and command and use them as slaves, he should not be considered a monarch, but a tyrant. As such, he need no longer be recognized by his subjects, especially if the States consulted. They may “verlaeten” him and elect in his place another to their protection as governor (overhooft).

This firm statement of principle is patently taken from On the Rights of Public Servants over their Subjects by Theodorus Beza. This successor to Calvin in Geneva published this treatise in 1575 on the question of when resistance to government was lawful. This was a thorny issue for ministers of the Word, for Paul, in his letter to the Romans 13:1-2, decrees the duty of submission to every worldly authority: "Everyone must recognize the authority of government, for there is no authority that does not come from God; even the present authority was instituted by God. Whoever opposes this authority, therefore, opposes an institution of God.

Beza wanted his writings to dispel the conscientious objections of Huguenots who were reluctant to take up arms against the lawful Catholic authorities after the massacre of their fellow believers in the Barthelomeüslacht of August 23/24, 1572. The opening words of the Plakkaat correspond almost word for word to a key passage in Beza's French treatise. Beza is not mentioned in the Plakkaat, probably in order not to offend Roman Catholic supporters by appealing to this notorious Calvinist. The only addition made on behalf of the States is that one may oppose a tyrant in particular ‘in deliberation of the States of the country’.

Philip could not be swayed

So the States actually play for God; they ultimately decide whether or not the monarch fulfills the conditions on which God appointed him. Modern times would naturally invoke popular sovereignty, but the sixteenth century was far from that. Rather, people were shocked at their own audacity, but they were unable “with humble verthooninghe” to “crush” the monarch. So there was no choice but to guarantee the ‘aengeboren vryheyt’ itself. Here, then, natural liberty is brought to the fore as a human right.Further on, humble attempts at reconciliation are referred to as the Petition of the Nobles of 1566 and recent consultations in Cologne. But Philip II, who is referred to only as “Coninck van Spaengien,” unfortunately remained intractable.

This is how tyrants fared

In passing, it is then said that it is sufficiently well known that on several occasions in various countries this innate freedom had already been defended against a tyrant.

Several experts to whom I asked what situations Van Asseliers, the editor of the Plakkaat was referring to, could not think of anything at all. They surmised that they were ancient "examples. That suspicion was confirmed when I consulted the (poor) scan of Beza's Du droit des Magistrats sur leurs Subiets on the interenet. Historical examples occupy most of the seventy pages of print. Exempla from Jewish history predominate, no wonder in a man who lived by Scripture. In addition, Beza refers at length to a variety of Greek and Roman cases of resistance to a tyrant, such as to dictator Julius Caesar, Roman emperors of the Nero type and to the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus. The latter was deposed around 500 BC, paving the way for the Roman Republic. An event already along than two thousand years ago still had argumentative value then, typical of a period in which lived with the past.

To contemporary examples of resistance or deposition of the monarch, Beza does not have very much to offer. The Danes, he says, had deposed their monarch (meant Christian II, 1523), the Swedes put their king in jail for mismanagement (Erik XIV, 1568) and the Scots had in their monarch deposed and sentenced to prison (Mary Stuart, 1567).

Philip deserved no better

The Plakkaat suffices with the global reference to precedents. Much emphasis is placed on the fact that precisely in our countries the monarch must abide by the pact made between him and the people. This, however, the king of Spain grossly violated. Examples of this breach of contract are given for pages, such as the cruelties and misdeeds of Alva, for example, the execution of Egmond and Hoorne and the self-willed introduction of the Tenth Penny, a tax rate that even today's market bidder can only dream of. We can leave out those historical digressions in the copy on scooped paper to be distributed to all Dutch schoolchildren.

Revolutionary measures

However, they do need to get the lock. In it, the concrete consequences of the preceding argument are drawn. The measures are truly revolutionary. Admittedly forced by necessity, the States General declare the Coninc of Spaegnien "expired of his lordship. The former monarch will no longer be involved in government in any way. It is no longer allowed to use his name as ‘overlord’. All those in authority are released from the oath of allegiance to him.

We laten in het prachtexemplaar voor de schooljeugd wijselijk de passages weg die refereren aan de onduidelijke toestand aangaande de soevereiniteit: aartshertog Matthias had die geweigerd, de hertog van Anjou was met de zuiderzon vertrokken en zijn terugkeer was hoogst twijfelachtig. Niemand kon in de stroomversnelling van die revolutionaire tijd voorzien wat er ging gebeuren. Alles was dus nogal voorlopig, maar de Staten–Generaal beperkten zich niet tot de negatieve maatregel van Filips’ afzwering. Ze eigenden zich ook formeel het hoogste gezag toe. De van de koningseed ontslagen ambtsdrager moesten ‘eenen nieuwen eedt’ afleggen waarmee zij tegenover de Staten ‘ghetrouwicheydt’ in de strijd ‘teghens den Coninck van Spaegnien ende allen zijne aenhanghers’ beloofden. Het koninklijke zegel werd vervangen door dat van de Staten-Generaal (de leeuw met zeventien pijlen). Exemplaren van het afgeschafte zegel moesten worden ingeleverd. Niet langer zouden er koninklijke munten worden geslagen. Natuurlijk werd het geld dat in omloop was niet meteen ongeldig verklaard. Dat was en is gewoon ondoenlijk. Zo bleef ‘communistisch’ geld ook nog geruime tijd in gebruik na de fluwelen revolutie van 1989. Maar het toe-eigenen van het recht op muntslag is hoe dan ook het aannemen van soevereiniteit.

Het Plakkaat eindigt met de opdracht aan alle autoriteiten om de besluiten bekend te maken zodat niemand zich achter het alibi van onwetendheid kon verschuilen.

Soevereiniteit bij de Staten

Dit manifest springt eruit tussen de talrijke geschriften die verschenen in de stroomversnelling die een revolutionaire tijd brengt. Andere kandidaten steken er mager tegen af. De Unie van Utrecht van januari 1579 is niet meer dan een militair noodverdrag. De Apologie van Willem van Oranje is precies wat de titel zegt, een persoonlijke verdediging van Willems aftrekening met Filips. Hetzelfde geldt voor het Wilhelmus. Het blijft bizar hele stadions te horen brullen dat ze altijd trouw aan de koning van Hispanje zijn geweest.

Wat zou nog mer in aanmerking kunnen komen? Er is nog de Deductie van Vrancken van 1587. In dit doorwrochte betoog neemt François Vranck, pensionaris van Gouda, stelling in de discussie over de soevereiniteit. Die hoorde volgens hem niet te berusten bij de koning van Frankrijk (met diens broer Anjou als representant) of Elisabeth van Engeland, vertegenwoordigd door Leicester. Al sinds achthonderd jaar hebben de ‘Landen van Hollant met Westvrieslant ende Zeelant’ door de Staten ‘de Heerschappije ende de Souverainiteyt der selver Landen wettelijck’ opgedragen aan de graven en gravinnen. Vranck, medestander van Van Oldenbarnevelt, eist dus voor de Staten de soevereiniteit op. Het woord republiek komt al in zijn geschrift voor, maar alleen als aanduiding van Venetië: deze ‘Republijcke’ is al even lang als onze gewesten vrij van overheersing.

Geboorte van republiek

Zoals bij zoveel staatkundige termen was de inhoud ‘republiek’ nog niet vastgelegd. Het Latijnse res publica betekende oorspronkelijk niet meer dan ‘algemeen belang’, in tegenstelling tot res privata. In de Nieuwe Tijd kon een monarchie best als een res publica gelden mits de vorst zich aan zijn plichten hield. Een ‘republiek’ was bovenal een gemenebest. Pas Hugo de Groot zou betogen dat ‘wij’ altijd een republiek waren geweest in de zin dat we nooit een permanente vorst hadden. Als bewijs grijpt hij nog verder in de geschiedenis terug dan Vrancks Deductie, die slechts achthonderd jaar terugging. Reeds de titel van zijn verhandeling bevat De Groots boodschap: Tractaet van de Batavische nu Hollantsche Republique. Hij maakte dus gebruik van de Bataafse mythe, die was ontstaan toen in de zestiende eeuw de herontdekte werken van Tacitus ook in Noordwest-Europa aandacht kregen Zijn Germania voedde het zelfbewustzijn van de over-Rijnse barbaren als edele wilden – Himmler heeft geprobeerd het oudste manuscript van de Germania voor zijn SS-heiligdom te bemachtigen. De Historiae zijn het enige antieke geschiedwerk waarin onze streken een prominente rol spelen. Tacitus vertelt daarin uitvoerig van de Bataafse Opstand (69-70), een rebellie die aantoonbaar meer dan een marginale gebeurtenis was; meer dan een kwart van alle legioenen werden eropaf gestuurd. In de eerste golf van belangstelling ging het er alleen of het eiland der Bataven nu in Holland of Gelderland lag. Maar in de laatste decennia van de zestiende eeuw werd de Bataafse Opstand ontdekt als een prefiguratie van de Nederlandse vrijheidsstrijd. De Bataven golden als echte vaderlanders die zich niet lieten ringeloren. De verheerlijking mondde uit in de Bataafse Republiek. En menigeen rijdt nog op een fiets met de mythische naam Batavus.

De Groot betoogt dat de Bataven uit Hessen de Rijn kwamen waren komen afzakken en zich gevestigd hadden in een onbewoond gebied. Als autochtonen waren ze ‘een volck vry van sijnen oorspronck, in een vry landt’. Naar Tacitus haalt hij Civilis’ rede in het heilige woud weer: ‘Laet dienstbaer wesen die van Syrien, Asien, en de volcken in ’t Oosten gheleghen, dewelcke den Koninghen ghewoon zijn.’ De Groot concludeert dat daarmee is aangetoond dat ‘de Bataviers van alsulcke maniere van regeringe een afkeer hadden. ‘

De ‘Bataviers’ lieten zich door de voortreffelijkste mannen regeren: door hen die uit het ‘het gemeene volck’ waren uitgezocht samen met hen die permanent onder de titel van koning of tijdelijk als ‘Veldt-overste’ waren aangesteld. Samen hadden ze het opperste gesach van de gemeene sake’, m.a.w. soevereiniteit in de res publica. Ze hadden dus eigenlijk al een soevereine Statenvergadering. Impliciet is de boodschap dat Maurits moest beseffen dat een Kapitein-Generaal slechts mandaat had voor zolang als de oorlog duurde.

Romeinen wijzer dan Filips

Uiteindelijk kwam het tot vrede tussen de Romeinen en Bataven. De Historiae breken af op het moment dat Civilis en de Romeinse commandant Cerialis aan weerskanten van een brug waarvan het middenstuk was weggebroken, onderhandelden. De vredesvoorwaarden zijn dus niet bekend, maar het oude bondgenootschap moet zijn hersteld. Zo toegevend waren nu de Romeinen in de persoon van Cerialis, net zoals Karel V was geweest. ‘Maer Philips sijnen sone hebbende een natuyre die niet te vrede en was anders als met een absolute macht, droegh een haet teghens alle Natien’ die hun vorsten de wet stelden.

De Groot gaat snel door de middeleeuwen heen, maar is zeker dat er ook toen een harmonieus samenspel was tussen vorst en Staten. De laatste vorsten hadden de soevereiniteit van de Staten wel wat ‘verduystert’, maar zij was in de vrijheidsstrijd wederom ‘klaerlick aen den dagh gekomen.’ Filips wiens eer lange tijd was ontzien, kon door smeken noch vermanen op andere gedachten worden gebracht. Dus hebben ten slotte de Staten-Generaal ‘op den ses-en-twintighsten Julij des Jaers 1581 verklaert, dat Koningh Philips ter oorsaecke van het verbreken van de Wetten van de regeeringhe, nae rechten ende metter daet van sijn Vorstendom was vervallen.’

Principes en pathos

26 juli de dag waarop Filips formeel en feitelijk werd afgezworen is voor De Groot dus de dag waarop de Staten-Generaal zich soeverein maakten. Moderne historici zoals Groenveld betogen dat het om tijdelijke maatregel ging in afwachting van Anjous mogelijke terugkeer. Pas op 12 april 1588 nam de Staten-Generaal in een resolutie onvoorwaardelijk de soevereiniteit aan. De betreffende resolutie zal echter niet sneller doen kloppen. Formeel mag toen de navelstreng met de Koning van Hispaniën inderdaad zijn doorgesneden, maar de geboorte had al eerder plaatsgevonden. Naar inhoud en vorm is het Plakkaat door principes en pathos het echte geboortecertificaat van Nederland. 26 juli moet de Nationale Verlatingsdag worden, met Afzweerfestivals en Verlatingsmarkten.